Disclaimer: This article is a bit old and does not apply to recent versions of the corona sdk. It is put here for educational purpose, showing how one may try to break into this kind of applications. It is not a magic formula for hacking all corona apps across all versions of the sdk.

If you haven’t played funrun yet, you probably will soon. Funrun2 is one of the best multiplayer mobile games out there. It’s one of these rare games where you can have all the fun from the very first game you play, but still stays enjoyable after month of playing it. It’s my favorite game on mobile and since I had some spare time, I decided to tear it open (yeah, that’s what I do to things I like). It was a bit harder than expected and involves some not so trivial hacking as well as a bit of luck. By the way, yes, all these buttons work.

The easy part

First I need to get my hands on the .apk file. There’s plenty of tools out there to do that, some of them are even open source.

An apk file is an archive, just like a jar or a zip so I can unpack it with regular unzipping tools. This gives me access to a well documented directory structure. The two things I want are the classes.dex file, containing java bytecode, and the assets directory. Reversing the first one allows me to get access to java source code so it’s pretty obvious why I want to look at it.

To understand why the second one is interesting though, you must consider that this game was built with a cross platform framework, namely corona. These kind of framework generally allow you to code your app with some scripting language that gets executed on every platform the same way. Therefore, unless the script is cross compiled to native language (which nobody ever does), it must be stored somewhere. That’s when the assets folder comes to play. It contains only a few images and this resource.car file which extension conveniently matches Corona ARchive. How cool is that ?

I open the file in a text editor and mostly get binary-unreadable-shit but there’s also strings like “lua.whatever.that.is.lu”. There are the scripts.

In case you don’t know: lua is one of the main scripting languages used in games with it’s open-source libraries and tools.

Now I still haven’t figured out where the images and sounds are (the corona archive weights a mere 2MB so it doesn’t contain any asset), but this will come later.

Things getting interesting

Trying to open the corona archive, I quickly realize it’s not a common archive format (even 7-zip can’t open it !). So there are two ways to go: finding the loading procedure in the java code or analyzing the file structure by hand. The first seems more reasonable.

But first, let’s decompile the dalvik bytecode into human readable java. These tools are helpful: dex2jar to covert the .dex to .class (dalvik to jvm) and jd to go back to plain java source code.

Now I have a load of java source code to look into, great! Let’s look for the string “resource.car”: no results. Looking manually, I quickly find corona’s source code in com/ansca/corona, that’s where the magic must happen. However, nothing is nearly dealing with a “resource” nor a “.car” file. I find however references to images. They were actually located on the device’s external storage (sdcard/Android/obb) in a .obb file. This is something common on android devices (that I wasn’t aware of before doing this hack), my guess is that moving resources allows the apk to be lighter and makes the internal memory footprint smaller. A .obb file is just a zip with a fancy extension. I can grab this file on a computer, edit the images/sounds/whatever and put it back in place. The game still runs with my custom images.

[caption id=”attachment_177” align=”aligncenter” width=”700”] Besides adding childish drawings to the game, there’s not much that can be done this way.[/caption]

Besides adding childish drawings to the game, there’s not much that can be done this way.[/caption]

I’m in a dead-end with the java code. Let’s give a shot at manually reversing the resource.car file:

I open it with a hex editor and quickly realize the format used is trivial:

First, a header to rule them all, then comes an index made of each file name + position (address) of it’s contents in the archive, then comes the data block with each file contents.

1 | [header] 16 bytes |

The resource.car file format

Now I didn’t have to code a packer for this format myself because luckily, someone already did that. So I grabbed this corona archive packer/unpacker which you won’t find a link to on my blog.

It turns out the archive contains uncompressed precompiled lua scripts, using luadec and then luac again you can decompile and then recompile these scripts which is very convenient. These lua scripts define absolutely every aspect of the game. From where a button might be to how fast a player can move and what a specific powerup does.

Injecting our custom resource.car in the app is a big deal because I could modify anything in the game.

First I try modifying something inside the precompiled lua scripts, such as a string since we can easily recognize them. If this works, I can later try to recompile one file from the (modified) source.

I repack the resource and put it back in the apk file, sign it with dex2jar (as explained here) and install it on my device. I launch the game and, with no real surprise, it crashes.

I figured there’s probably some kind of check performed against the archive to guarantee integrity. However, the loader is nowhere to be found in the java source. This battle is lost but not the war.

Going down

Yeah, maybe Di Caprio is right, we need to go low-level and find this resource loading procedure.

Inside the .apk, there’s another directory called “lib”. It contains architecture-specific libraries. You’d usually build a native library either when you have no choice but use C (for instance, lua is written in C) or when you want higher-than-java performances (for a game framework, it makes sense).

In this lib folder, there’s some lua libraries, but also random libs for sound, video, analytics and whatever. Most importantly I find here a lib called libcorona.so. Let’s quickly open it with a text editor to search for the string “resource.car”, bingo!

I’ll have to disassemble the lib in order to understand what’s happening in there. It turns out, there’s an amazing tool that does this and it’s called IDA. It’s more than a cross-architecture disassembler, it does lot’s of stuff but for my purpose I’ll just use it as a disassembler. It handles libcorona very well and kindly gives us the assembly code.

FYI: I picked the armeabi-v7a version so what follows would be different different with an apk targetting another platform

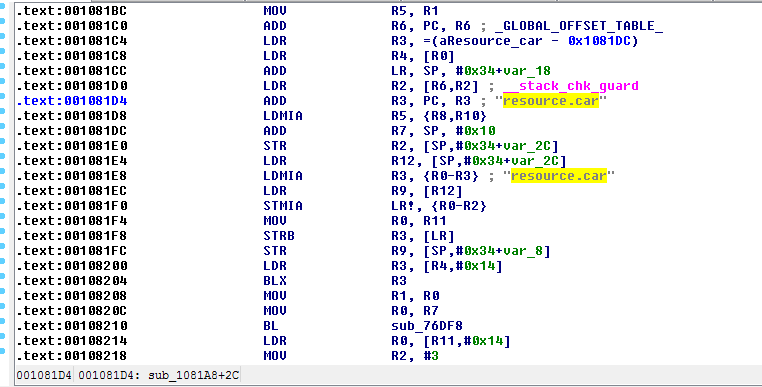

I look again for the string “resource.car” and find it referenced at offset 0x1081D4.

[caption id=”attachment_180” align=”aligncenter” width=”762”] The only piece of code referring to “resource.car”[/caption]

The only piece of code referring to “resource.car”[/caption]

It took me a while to figure out how things worked, but at some point i had a theory:

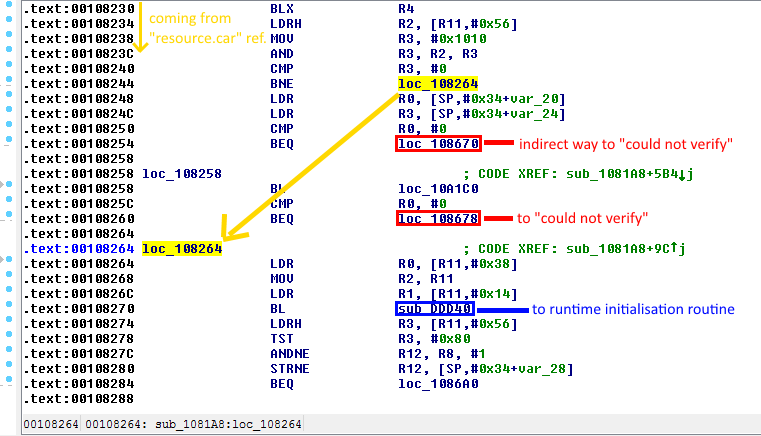

From the occurence of “resource.car”, I clearly see two execution paths: one that leads to a portion of code referencing the string “could not verify” and exiting, and one that leads to a subroutine that I deduced was meant to initialize the lua runtime or something like that. What stands between them is a fragile Branch No Equal (BNE) that we would like to turn into a rock solid Branch.

[caption id=”attachment_181” align=”aligncenter” width=”761”] Take the yellow jump to get to the blue subroutine and avoid the nasty red branches[/caption]

Take the yellow jump to get to the blue subroutine and avoid the nasty red branches[/caption]

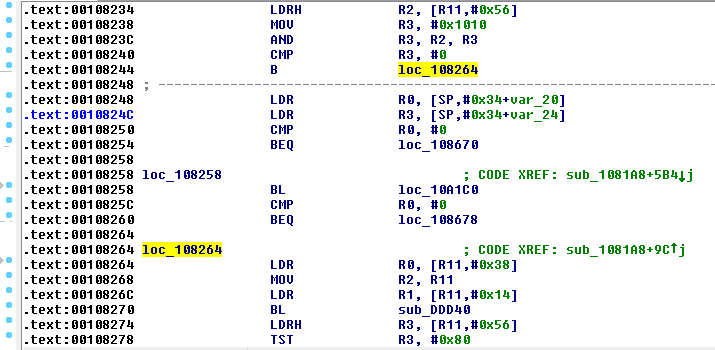

Looking at this document and some other branch instructions around in the code, I deduced that I needed to change byte x108247 from 1A to EA to turn my BNE into a B. Going back to my hex editor (I should really learn how to use IDA properly some day) I change the aforementioned value.

[caption id=”attachment_182” align=”aligncenter” width=”715”] It’s a branch![/caption]

It’s a branch![/caption]

Now let’s pack our patched lib back into the apk, sign it, install it, run it… It runs! Let’s see if our custom value is used.

[caption id=”attachment_185” align=”aligncenter” width=”700”] First time ever a guessed binary patch works upon first try.[/caption]

First time ever a guessed binary patch works upon first try.[/caption]

Let’s try the full pipeline: modify the lua source code, compile it, repack the .car and place it back in the .apk. It works provided we use the proper luac version (a quick search for the version string in liblua.so saves you the guessing). That’s it, the path is paved for hours of fun modding the game!

Conclusion

I had seen many game cheats and always wondered how they actually work, now I know at least for this one. To illustrate this article, I managed to strip all ads from the game, create a speed hack, fly mode, and unlimited powerups. Hacking the in-game money is harder because only the server issues coins, so even if you trick your phone into thinking you are rich, the server knows how much you really have.

I’d like to emphasis that I personally think buying or downloading a cheat for a game is lame and those who do that just deserve a trojan. However, hacking a game is really something fun that one should try. It requires patience, and a capability to keep a clear mind even after hours of work leading nowhere.