This is absolutely not what this chip had been designed to do. But here it is: the WiFi multiplayer game of pong on the ESP8266.

This project turned out to be much more challenging than writing a regular desktop game of pong due to the limitations of the platform. But difficulty is what makes a project fun isn’t it?

How it works

This project uses the NodeMCU firmware, which lets us write the application using lua scripts, while the heavy lifting is handled by native modules in the firmware.

We also use U8G2 to control a SSD1306-based LED screen of 128x64 pixels. Two push buttons are added for user input.

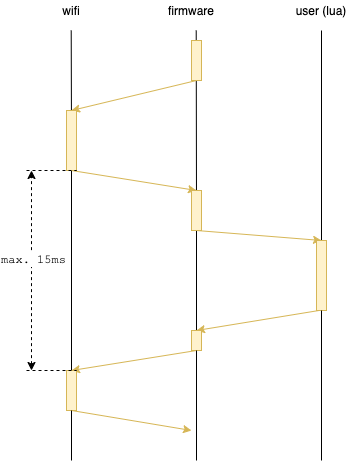

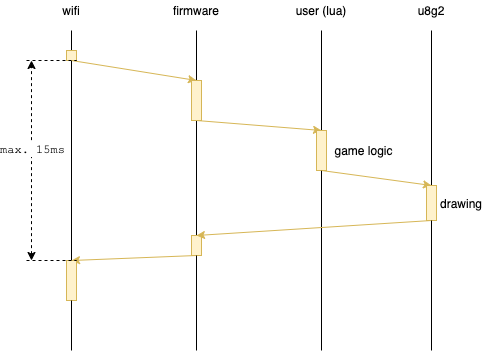

The ESP8266 has only one CPU core which must handle both the WiFi stack and the user code. The SDK supporting NodeMCU is event-driven and non preemptive. This means that it maintains an internal queue of event handlers and runs one handler at a time. If there is something urgent in the queue, the SDK can not interrupt the current handler to do that urgent thing; It must wait until the current handler has finished.

In practice, any invokation of our lua code must complete in under 15 milliseconds, otherwise the WiFi stack might starve and cause the device to crash and reboot.

Differential rendering

One major consequence of the above is that we need to consider the time it takes u8g2 to update the screen.

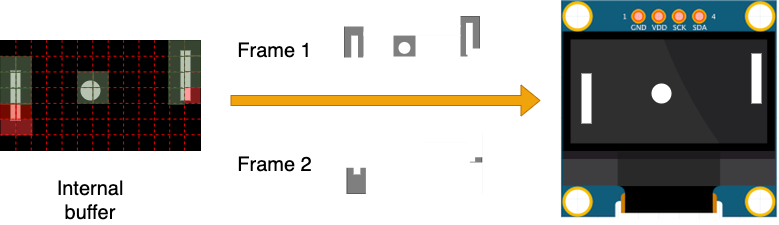

The graphic library works with an internal buffer. All drawing operations are made against this buffer. Then, you need to call a function to actually draw this buffer on the screen.

1 | -- Make changes to the internal buffer |

The problem with this approach is that updating the whole screen takes almost the entire time available to run our game loop. There is not enough time left to process inputs, update the state, compute collisions and redraw the objects.

Fortunately, full buffer updates aren’t the only way we can update the screen. u8g2 cuts a screen into tiles of 8x8 pixels which we can update individually using updateDisplayArea.

The first optimization we make is to mark tiles which have changed and only send those tiles instead of the whole screen.

However, even with this optimization, there comes times when too much of the screen has changed at once and the rendering still takes too long and crashes.

The second optimization is to keep track of time while sending the tiles to the screen. When we get too close to the limit, we stop sending new tiles and continue from where we left in the next render cycle.

Here is the pseudo code for the rendering logic. We keep cycling through the tiles and stop when we have rendered the whole screen, or when there is no time left. Only dirty tiles are effectively rendered.

1 | i = 0 |

Miscellaneous

There’s plenty more things in the code which I did not discuss here, like how the game logic works in multiplayer as well as various other performance tricks.

Check out the project on GitHub if you want to dive deeper into the code or if you want to run it yourself.

Happy hacking!